What We Carried: Fragments from the Cradle of Civilization was funded in part by The Regional Arts and Culture Council (RACC).

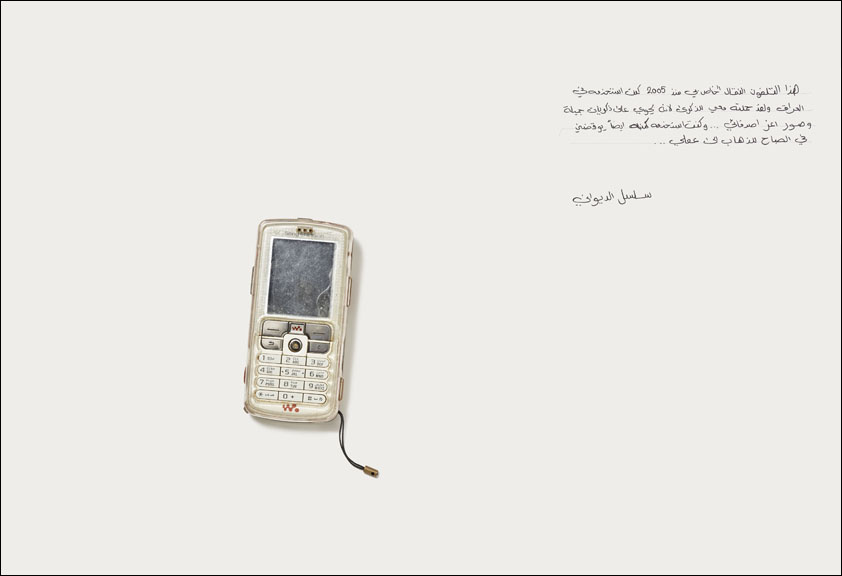

“The camera has two capacities,” remarked John Berger, “to subjectivise reality and objectify it.” These two capacities are rarely as evident as in the collection of images by artist Jim Lommasson, titled, What We Carried: Fragments from the Cradle of Civilization. The result is an alternative photography, one that functions as a metaphor for our social landscape. At Lommasson’s request, Iraqi refugees share an item that accompanied them during their immigration to America. He then makes a print of the item against a clean white background. The effect is startling. Parallels abound. The blank slate entirely absorbs, or perhaps, assimilates whatever trace of the memories and dreams that make this item a subject of belonging.

Over four million Iraqis have been forced to flee their homes since the 2003 U.S. invasion. Iraqi refugees didn't leave their country to get a better job, or because of a natural disaster, or an act of God. They left because of an act of Man. They left because of a brutal dictator and industrial warfare that has virtually destroyed their country. The long journey from Iraq to the U.S. may take months, sometimes even years, and includes refugee camps, piles of documents and possibly a few bribes.

Lommasson then returns this austere print to his collaborator, and invites them to contextualize it. The participant’s marks render the sanitized glossy images powerful, vulnerable, and breathtakingly individual. A trace of the significance, of the memory, is cast across the signified–sometimes reading to the eye as an adornment, sometimes as a lost caption, or a last minute edit before going to print, while simultaneously evoking the narratives around classification, defamation of art, and graffiti.

As the National Museum of Antiquities in Baghdad was being looted of objects from the civilizations of ancient Mesopotamia-- including the tablets with Hammurabi’s Code, the world’s first system of law–Iraqis were fleeing their homeland with a few common personal mementoes to collect their past and reconstruct their future.

Lommasson then photographs the rectified prints, producing a third image. The added layer destroys the original, or rather reproduces it. And the other twin capacities of photography reveal themselves: preservation and surveillance.

What We Carried is an engrossing collection of photographs that speaks to displacement, resilience, liminality, xenophobia, rendition, human interdependence, freedom, memory, and to the purpose of photography itself.

Artist Jim Lommasson works to “incorporate photography into social and political memory (instead of using it as a substitute, which encourages an atrophy of any such memory.)”

– Millicent Zimdars