Several Layers of Beauty

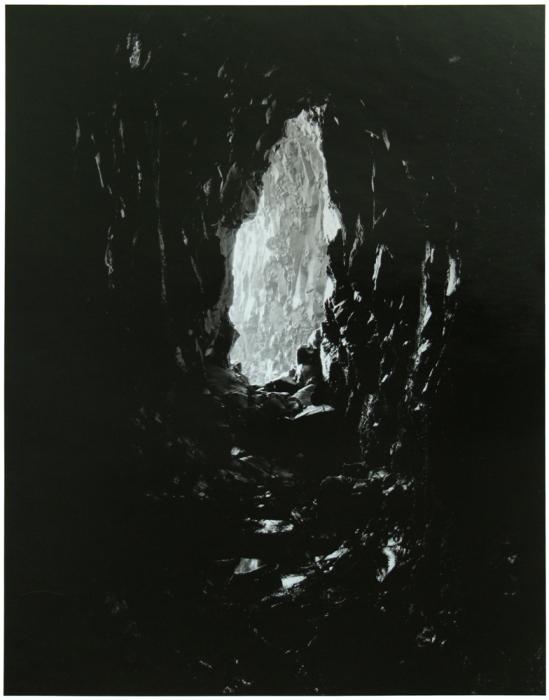

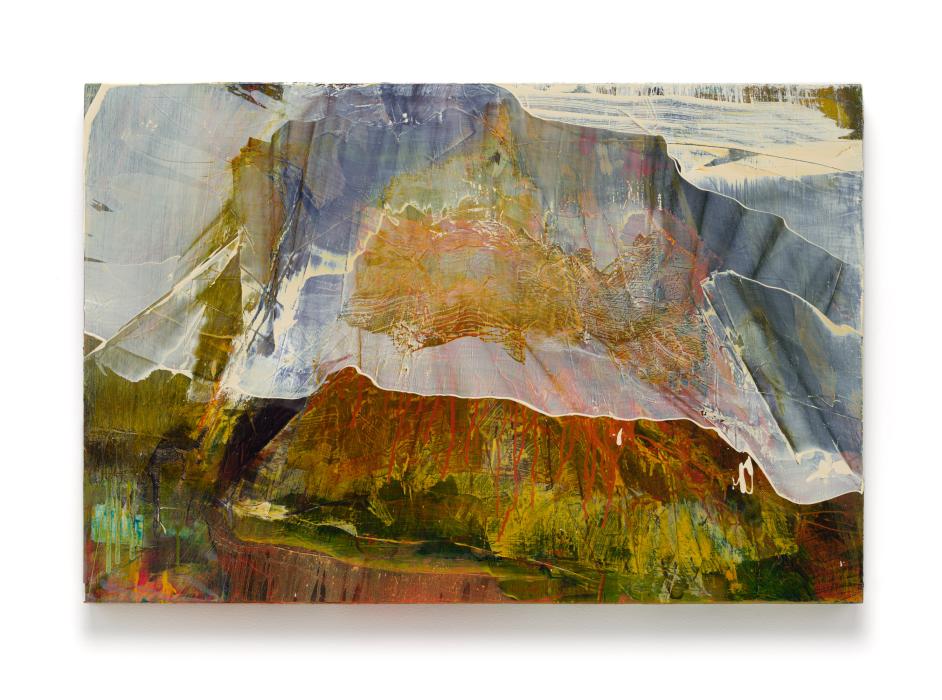

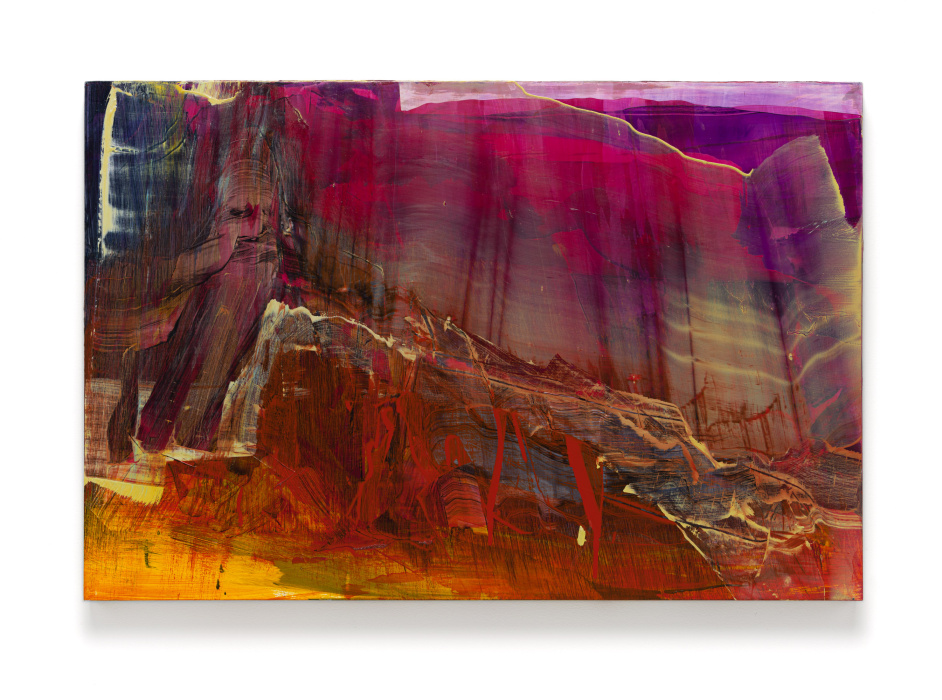

This exhibition brings together new paintings by James Lavadour with a few older photographs made by Terry Toedtemeier, who died in 2008. Together, the two bodies of work speak eloquently to the talents of both artists and to the beauty of the Pacific Northwest: Lavadour’s through soaring compositions alive with brilliant color and form; Toedtemeier’s through the subtle tonalities of his black and white prints. The two men knew each other, though not well, and shared interests in music, food and, more importantly, the geology of Oregon, their lifelong residence. For each, an awareness of the land’s importance and a curiosity about the geologic forces that created it, came in childhood.

Some years ago, Toedtemeier wrote the following in a letter to curator Toby Jurovics:

The photographs that I create are simultaneously about several layers of beauty: the print, the subject, and the subject context (geology). …That the land is beautiful is the strongest clue I have towards a greater sense of unity.”

These words (minus those specifically about photography) might equally well be applied to Lavadour’s paintings and his process. His paintings are shaped by a deep knowledge of the land that has surrounded him and his ancestors for generations: a knowledge that lives within him as a kind of cellular memory. Thus, in painting, his gestures unleash that memory. The acts of laying down paint, of scraping, of building up layers, often over long periods of time, replicate the ways in which natural forces and human histories have shaped the rivers and cliff faces, the rocks, and the hills that he sees on his almost daily drives. In his works, past and present collide in forms, spaces, and actions built of paint. They speak to place and they speak to history.

Lavadour’s paintings and Toedtemeier’s photographs also contain what I can best describe as vastness. This vastness is spatial, but it also incorporates the depths of time as they are revealed through the contours of hillsides and mountains, through the striations of rock, and through the evidence of human presence: the geologic history that can be read at a roadcut, for instance. (Lavadour has talked recently of his interest in making paintings that look up at rather than across a landscape, as one scans a cliff face—or said roadcut. I am reminded of his long-held interest in Chinese brush paintings, designed to be read from bottom to top.) Neither artist has sought grand vistas or limitless horizons. Instead, they have found vastness within the confines of a self-defined territory. For Toedtemeier, it was the basin and range country and the basalt flows and forms shaped by the Missoula floods; for Lavadour it is primarily the Umatilla Indian Reservation and surrounding lands—lands he alludes to in the title “The New Ghosts of Ceded Boundaries,” referencing the thousands of acres promised in an 1855 treaty to the Cayuse, Umatilla, and Walla Walla people, but lost in subsequent government actions.

Like the places that inspired them, these paintings and photographs are the visual records of a quest to find “a greater sense of unity.” That they achieve that unity in themselves is a gift to us, the viewers.

Prudence F. Roberts

March 2022