In 1957 the State of Oregon outlawed the use of splash dams on Oregon waterways. Splash dams were built on rivers and creeks as a way to back up water in a sufficient volume to propel logged trees downstream. The flood caused by the sudden gush of water, plus the massive number of logs, scoured the waterways down to the bedrock, thereby making those streams inhospitable to the spawning salmon that required gravel beds (redds) to lay and fertilize eggs. Only after a series of lawsuits by anglers and environmentalists was the practice terminated nationwide.

Often the rush of logs downstream would cause logjams. When this happened, log drivers (men in the employ of the lumber company) would have to climb out onto the jam and free it up. This was very dangerous work and required care and skill. One false step could find one trapped, crushed or drowned underneath tons of wood. The drivers were the highest paid and most dead. And from this came birling, or log rolling, an innocent enough competition that is still played at logger games.

It does not take a great leap to fix a partial etymology of the title for Vanessa Renwick's current installation at PDX Across the Hall. However, instead of connoting a dangerous failure, nowadays the phrase has nearly the opposite meaning, suggesting that an endeavor is considered foolproof. Once a catharsis and testament, the conceit of innocence brings unexpected consequences. And still the rivers, and therefore the fish, have not yet recovered.

This is not to say that Renwick's installation has much, if anything to do with the state of rivers, and if there is an environmental advocacy underlying the work, it is more concerned with the state of the forests as a whole. Even then, this is not the central thrust of the work. Instead, Renwick provides a perception of nature that is more personal, and to go along for the ride takes commitment.

Any given month in Portland, one can find several exhibitions that work around relationships with nature. For instance, Charles A. Hartman Fine Art has Ansel Adams, Elizabeth Leach is showing Shane McAdams' Micro Chasm, and NAAU has an exhibition by the Appendix collaborative (specifically Maggie Casey's discreet piece, Virus). Think of it this way: Adams and Appendix had a baby and it looks something like McAdams. Adams goes for the vista, Appendix brings us in for a close look at the flora and geology, and McAdams combines the two. All-in-all, very artsy, and it may be that we need to examine our relationship with work like Adams’ to move away from idealizing, even fetishizing the landscape to the point of exhaustion where the results become mundane.

Vanessa Renwick's installation at PDX Across the Hall is no different in those respects. Where it does differ, however, is demanding attention to an aspect of nature from which many have distanced themselves or lost altogether: the concept of natural time, or, if you will, a slower pace. And if one breezes in and out of the gallery, that aspect of the work, particularly the video components, will be missed. Renwick seems to have anticipated this and has provided a couch in front of WOODSWOMAN, and some large throw pillows to lay on while watching the video segments on the ceiling that are part of the installation FULL ON LOG JAM.

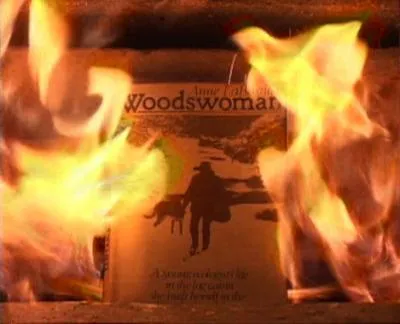

The couch was comfortable enough to watch a book burn in a gas heater. The book, Woodswoman, by Anne LaBastille was the author’s first about her life in the relative isolation of the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York. At intervals in the video, Renwick adds text to tell the story of her own relationship with the book. It seems she tried to sell it to Powell's Books twice, to no avail, lent it to person, and was given it back along with a scathing review, eventually deciding to burn it, a proper burial, so to speak, after mentioning that arsonists burned down Ms. LaBastille's barns and the aged woman now suffers with Alzheimer's. The fireplace entranced the viewer throughout the otherwise uneventful video, yet the fire may have provided the hypnosis required to slow the person who might have had an agenda to be elsewhere, thereby allowing for one to linger just a bit longer and sit through another video in FULL ON LOG JAM.

FULL ON LOG JAM itself is a makeshift installation: camo plastic tarps protect the floor from a cord and a half of firewood, and the wood and two pillows are mounded around a box with a projector pointed at the ceiling. Uncertain of a narrative and therefore a beginning and end, the piece is pulled together not by the forest scenes but by a short documentation of a Native American splitting firewood at a very, very, slow yet methodical pace. Using primarily a wedge and a hand sledge, and occasionally a maul, he never misses the log. He is talking, as are others in the background, yet one somehow isn't listening, again entranced, that is until he asks the videographer, "Do you know Gail?" When the answer is negative, he simply remarks, "She's a neighbor." If she is not known then the outsider need not be informed of anything more. Suddenly, we're no longer welcome to watch him at his work.

In the artist's statement for the installation, much is made of having sex in the woods, and while that may be a fantasy for outdoorsy types, the only sexual references in the whole exhibit were two text pieces, a sculpture in a window case and another wall-mounted piece indoors. A bumper sticker has been altered to read "Wilderness: A great place to fuck and fuck," and there is a small red monoprint with the words "Get Off." The sculpture, flat as a board (knot), represented breasts and a pubis. Both text pieces were done in all capital letters (for which Renwick seems to have an affinity), which lent a certain emphasis, but the alteration of the first, plus the double entendre of the monoprint and the sculpture were more playful —perhaps foreplay — than sexual. For that matter, FULL ON LOG JAM can also be seen to have this dual meaning, but again, the sexuality is suggested only in the title.

There are more directed, albeit non-sexual, associations between other aspects of the installation that suggest more environmental concerns: the FULL ON LOG JAM video has vignettes of a decaying trees, forest canopies, a waterfall and trees reflecting in a calm body of water; the fire that burns the book can relate to a series of photos that show the aftermath of forest fires, and there is a piece of charred lumber (Redeem) that hangs between the video and photos. Yet, the resonance goes no further, unless one considers that the proximity of the burned forest photos and sculpture to WILDERNESS and GET OFF is designed juxtaposition. If anything, the destroyed forest is a lost love, which might bring more bearing on the titles for the photos, The Wise and Seen It All, memorialized, but also romanticized in a manner that is antithetical to sex.

There are more directed, albeit non-sexual, associations between other aspects of the installation that suggest more environmental concerns: the FULL ON LOG JAM video has vignettes of a decaying trees, forest canopies, a waterfall and trees reflecting in a calm body of water; the fire that burns the book can relate to a series of photos that show the aftermath of forest fires, and there is a piece of charred lumber (Redeem) that hangs between the video and photos. Yet, the resonance goes no further, unless one considers that the proximity of the burned forest photos and sculpture to WILDERNESS and GET OFF is designed juxtaposition. If anything, the destroyed forest is a lost love, which might bring more bearing on the titles for the photos, The Wise and Seen It All, memorialized, but also romanticized in a manner that is antithetical to sex.

It is clear from Vanessa Renwick's statement for this exhibit that she has a personal relationship with trees. Her enthusiasm is palpable and she perhaps communes more intensely with trees than the rest of us. What special intimacy may be plain and simple to Renwick has a difficult time coming across to viewers. Still, as easy as falling off a log as an exhibit does contain the foundations of a narrative. What is unclear is whether more of the story needs told, or edited. As a successful filmmaker, Renwick knows that narratives take time to develop, just as it does Nature to restore itself after a disaster.

-Patrick Collier