Full Text Here: http://bombsite.com/issues/1000/articles/6836

Anna Gray and Ryan Wilson Paulsen, along with their two-year-old son Calder, are a family art team who create works with a cool analytic aesthetic in a multitude of media, including photo-based indexes, textual mixed tapes, associative lectures, and mass mailings. Their work hinges on the linguistics of text and image, and contains a healthy dose of humor. Their latest exhibition, Maybe It Takes a Loud Noise at PDX Contemporary Art, considered themes nested in the rhetoric of belief and protest. We connected online while they traveled away from their home in Portland, Oregon soon after the close of their exhibition.

Mack McFarland You cite the texts you read as major influences for your work, in the way that French Impressionists found inspiration in the landscape. You also mention the structure of the book and I have heard, or maybe read, that you feel like your works translate well to the book form, which is lovely and kind of old-fashioned. Do you think your projects work well for tablet computers or smart phones?

Anna Gray + Ryan Wilson Paulsen Maybe some of our work does. Some doesn’t. (We have been working slowly on making a collection of GIFs, but that is probably not exactly what you’re talking about.) We do think about how our works play out on screen, but still involuntarily find ourselves thinking about the final form of what we make as a book or publication.

We often make things in large series that are meant to function like swarms. Conceived as, and intended to be viewed as, one cumulative body, they are also designed to break apart and still hold meaning. (This comes less from thinking about the actual representational platforms i.e. tablet, phone and more from the way images and texts are viewed and aggregated on the Internet.) We accept the conditions of having an online presence, we want our work to be subsumed and re-articulated. We might even go so far as to say that people who want to forbid that kind of movement and transmission need to grow up.

It is a difficult position, in some ways, to be in between these technologies. An obsession with books might be the wrong idea for artists like us. Maybe books are past the point of compelling remediation; maybe they are too nostalgic, fetishized, impotent. Then again, in them we might find a way to resist the destructive speed of current information technology, to endorse reading over networking, vibrant materiality over displacement and intangibility. Also, as a nod to our end-time friends, we would like to remind everyone that if ecological and energy disaster does strike in our lifetime the book will fare better than the Kindle.

99_protestbookpage009.jpg

Anna Gray + Ryan Wilson Paulsen. (page from) Can These Antiques Ever Prove Dangerous Again?, 2012.

MM Subsumed and re-articulated, right, as in one of your 100 Posterworks, “Dear Author, Do you think that one day you might include us in one of your books? We are already half-fictionalized.” Is that what you mean by, “artists like us”?

AG + RWP Artists like us = young(ish) artists who are trying to sustain an art practice and a family, who are half in life and half in art—artists who are and probably always will be “emerging.”

MM Your practice seems to come from a place of inquisitiveness, and the resulting pieces and bodies of work seem to imply that you are seeking further questions from the viewer. What would you most like to be asked?

AG + RWP That’s a good question . . . In one way we would love to be asked, “Can I have this?” But we think it is less about having the viewer ask us questions directly, and more about causing them to question their own assumptions ’cause that is largely what we are doing with our work.

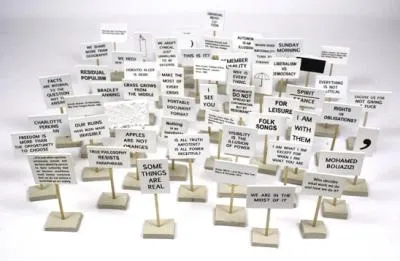

MM We talked about the structure of the book and its influence on your work, but in this exhibition I also see you working with other forms or locations of language. I am thinking of the protest signs in Can These Antiques Ever Prove Dangerous Again? which consists of several—I am sure you can tell us how many—miniature placard signs, about six inches tall, arranged on the floor and photocopied in a book of the same title.

AG + RWP There are 101.

MM These signs carry, as you describe, “proposals, phrases, and foreign ideas” such as when does rationality turn to tyranny?, or i am a sign, or I was taught to think, and I was willing to believe, that genius was not a bawd, that virtue was not a mask, that liberty was not a name, that love had its seat in the human heart. or excuse us for not giving a fuck. You write of them: “they all ask the same co-opted question—a question that genuinely approaches notions of obsolescence, ineffectiveness, smallness, slowness,” and that you appreciate these for the reflection they allow, yet here too there seems a desire for something time-tested, effective, grand, and immediate. I think the question here is, are these puny signs reflecting yours (and a whole generation’s) frustrations with not necessarily Occupy, but the methods for being political in this era?

AG + RWP Yes. How is one political now? How can we afford to be? We recently read an article in Art In America with some relevant words from Philip Guston. Guston questioned “whether it’s possible to create in our society at all.” He said, “Everybody can make pictures, thousands of people go to school, thousands go to galleries, museums, it becomes not only a way of life now, it becomes a way to make a living. In our kind of democracy this is going to proliferate like mad.”

It seems like maybe he misplaced the word democracy here, capitalism might have been better. Anyway, there is a real feeling for us of being in a corner . . . We aren’t saying they are completely ineffectual, but these rallies and marches (with permits and approval), pickets (with no real blockades) all feel impotent. We need a confrontation from all sides. We need to intervene not decorate. Or we need to set direct confrontation aside and build some alternatives, to find the alternatives that already exist in our system and boost them up.

There is a new push to create autonomous zones within the gaps of state control. This is what Zucotti Park was, and Occupy has made a lot of things visible and tangible that were invisible or intangible before. Class inequality, debt, corrupt systems of exchange and government, etc. are much easier to talk about and to see.

People have started to create alternative organizational structures, which in turn makes it feel as if there might be openings, tiny fissures for art to squeeze through and expand. Artists can envision new ways to live together for the indefinite future. This sounds lofty, and it is. Our artistic gestures are much more humble, traditional—subtly, softly subversive if subversive at all. The objects we make feel most alive when we use them as props. That is when it feels like we are doing our real work: when we use our works as illustrations, thought bubbles, and power-point slides in performing the things we question or rail against.

MM Can you tell me about the title of the exhibition: Maybe it Takes a Loud Noise?

AC + RWP Maybe it Takes a Loud Noise was chosen because its ruminative tone reflects our general attitude. All the works in the show center around a different problem, or set of problems, and this title was an attempt at an answer. In a larger sense, it is a question about what works to effect change or direct focus on a mass-scale. What can build a conversation? What knocks the mechanisms of industry, politics, and everyday life out of their parallel droning orbits?

We’re observing an active culture of resistance in the world right now, but sometimes we see that movement being wholly ignored, redacted in real-time. The title also nods at the visual and aural quietness of our own work in the show, a tacit acknowledgment that (though we aren’t trying directly to effect change with these objects, but rather to open a space of contemplation) we too are probably failing.

MM You’ve placed two different works titled Do We Need New Metaphors? as, if I may, bookends to the show. Both 60×40 inches and graphite on paper, one is a drawing of a book standing upright—its pages facing us, the other a drawing of Horatio Alger Jr.’s grave. It’s a question that will always plague artists and songwriters the most. The image of the book brings to mind the death of print and the ways electronic and Internet culture have changed the metaphors of this century. Alger’s grave points to another death, that of the middle class and the rags-to-riches stories that spur on young artists and athletes still today. So I ask you, do we need new metaphors?

AG + RWP Yes and no. We want to interrogate our own belief in existing metaphors. Also a clarification: the sentiment is similar but the titles of the drawings you mentioned are actually different. The one of the book is: Do We Need New Metaphors? and the one of the grave, doesn’t ask, it just plainly states: We Need New Narratives. We designed both of the drawings to appear as post-mortem renderings, as funeral portraits, visualizing the ghosts of myths and metaphors past.

We Need New Narratives grew out of a sign we were carrying at protests that read “Horatio Alger is Dead / We Need New Narratives.” We were thinking about how to envision our own individual and collective futures, and realizing how difficult it is to navigate blindly, building a structure of one’s own amongst the privatized ruins of our economic, educational, and political systems. It seems a more difficult task than simply plugging individual circumstance and sensibility into semi-functional, progressive, existing programs.

9_alger.jpg

Anna Gray + Ryan Wilson Paulsen. 100 Posterworks, 2009 – 2011. 11×17 inches. printed poster.

It’s bizarre that stories, like Horatio Alger’s rags-to-riches story, come to stand for something that they never actually represented in the first place. The characters in the stories who supposedly pulled themselves up by their bootstraps couldn’t have done so without the kindness of some older and richer character. The narrative is one of dependence rather than rugged individualism, but that is the power of myth.

The other drawing asks a simple question, one with an obvious answer. We are of course already operating with new conceptual metaphors that don’t follow the structure of the page, or verbal language as it is represented in a book. We don’t think in terms of linguistics—the scaffolding of a paragraph, or any of that—we read in a different way now. We search, scan, and scroll, navigating with a series of intersecting algorithms. With search engines, location-aware technology, social media databases, we read through indexes and prefixed programs where the systems of formation and construction are hidden. The mathematical sequences that underlie our forms of life come into focus as metaphorical structures for our thinking and perception. They are about non-lineation, automation, externalization.

So the title also represents a question about the value of dead metaphors, and reveals our desire to question these emerging metaphors and whether the metaphor itself, a form based in comparison and substitution, is losing validity or power. How much are we able to choose the ways we understand the world, our orientational, and ontological patterns, programs, and relationships? Who or what makes these choices?

MM Perhaps my mistake was Freudian. Or maybe in light of your response, “Metaphortean,” that neologism by Carl Diehl, which alludes to a drawing together of new and used (obsolescent) media in the hopes of uncovering overlooked or hidden connections, yet all the while obfuscating the findings in near conspiracy theorist prose. Not to say you are obscuring or paranoid, it’s just that when we delve into the construct of knowing and the real, all the Baudrillardian hairs stand up on the back of my neck.

AG + RWP What other kinds of hairs do you have back there? Baudrillard was a conspiracy theorist! Really, it seems like maybe the aesthetics of conspiracy theory have a new relevance doesn’t it? (Everyone is always obfuscating something. Think about anti-regime activists and independent journalists in Syria. Some of them were honest about their sympathies and selective gaze, aiming their cameras and stories at authoritarian violence while ignoring a lot of rebel violence.) One of the amazing things about aiming a wide gaze and looking for hidden connections is that it does allow us to see real conspiracies. Look at the Libor scandal, look at info graphics about who debt benefits and at what cost, look at all three of our artistic and professional positions in relation to this interview. We are conspiring to get our words, our work, and that of our colleagues in front of others’ eyes. Where is the distinction between evil conspiracy and healthy cooperation?

MM Conspiracy is in the eye of the beholder.

Mack McFarland is the curator for the Feldman Gallery and Project Space at the Pacific Northwest College of Art. He is also an artist who creates his home in Portland, OR. McFarland has been quoted as saying, “Wherever I am, I’m making.” His post-studio mantra has taken him to archives, karaoke microphones, canoes, and into his studio.